A little while back one of my clients asked me to help them create a “solid project plan” for their innovative project. My simple answer: Don’t!

Creating a “solid project plan” or any type of lengthy “plan” document will set you up for failure. It goes like this: you have had a brilliant idea for an innovation, got some internal or outside funding writing a (grant) proposal where you promise the world. And yes, congratulations! Your hard work paid off and you have (some) money, a team and the green light to go ahead!

Are you a good project manager?

As a good project manager you now need to create a detailed plan to make sure that everything goes right from start to finish, to fill in all the details, to define the deliverables and be in full control. Right? Wrong. You are following the traditional ‘waterfall’ method that assumes that everything is know in advance and can be planned with certainty. That is actually the opposite of innovation! With innovation you are trying something new, exploring, learning, figuring things out. So you need room to maneuver, to change your mind, go in a different direction.

And on top of that: spending all that time on creating a project plan, filling in all those details that you possibly cannot know yet, primes you attach to these ideas, to defend them at all cost. You have created a fairy tale and you believe it. And your manager, donor, investor, or whoever is demanding that you deliver, is believing the fairy tale as well. The fairy tale will not lead to happy ever after, it will turn into a horror story.

What to do instead? Set up a solid innovation process! A process that gives you the much-needed “solidity” for you to hang on to in these times of uncertainty, doubt and fear of failure. A process that stays in place no matter how much the “content”, the innovation itself, is shifting beneeth your feet.

In this innovation process uncertainty is made explicit, doubt becomes a strength and fear vanishes in thin air.

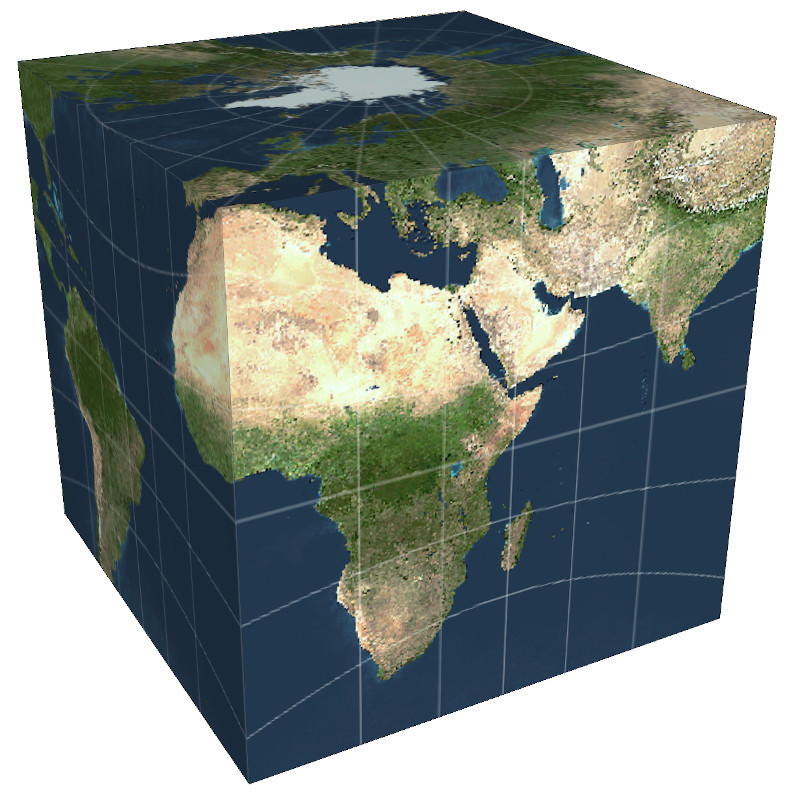

We think the earth is a cube

Ash Maurya calls this process “Iterating from Plan A to a Plan That Works”. For Eric Ries this is the Lean Start-up cycle, a learning process that eliminates ‘waste’ (of time, money, effort, …) as much as possible. In Design Thinking it is called the “diamond” of diverging and converging in iterations.

Some years ago I attended a conference where a start-up founder on stage used a brilliant metaphor to illustrate this point. He said: when you start out with your initiative, you think that the earth is a cube. Only by learning more and more about it, you later find out that it is actually a globe.

[Image copyright 3D Warehouse]

Note: some people believe that the earth is actually flat. Please do not use the True Facts in this post to start a “Cube Earth Movement”!

In my work with many teams I found that one thing is key to understand and work with: assumptions. A lot of teams do not understand what these are and that they even exist. They are “unconsciously incompetent”. This is how I explain it.

At any moment in time you and your team have what I like to call a “working theory” of your innovation in mind. This is more-or-less (likely less) complete, coherent and sensible ‘mental model’ of what the problem is you are solving, the solution to solve it, who to solve it for, how to create a sustainable financial model for it, how to scale it up, etc. Whether you are conscious about it or not, whether you want to or not, you have this working theory. Probably it is not complete, it holds conflicting ideas, it has holes, it has risks and uncertainties. And the rest of your team also has a working theory in their minds. Which is no-doubt different from yours, but hopefully there is some overlap.

A success story takes 5 steps

Now, the first step is to become aware that you and your team each have this working theory. Start to make the working theory explicit and inter-subjective (or: talked about). Design Thinking gives us many tools to make various ‘views’ or ‘perspectives’ of the working theory explicit in a visual way, for example: Personas, User Journey, Stakeholder Map and the Business Model Canvas.

The second step is to realize that the working theory contains assumptions. You can make these assumptions explicit by identifying and labeling them in the Design Thinking visuals.

“Assumption: something that you accept as true without question or proof” (Cambridge Dictionary)

Then the third step is to talk about and document (list) the risk of each of the assumptions: what is the possibility that this thing is not true? And if it is not true, what would be the impact of that? An example: let’s say your idea is to develop an app for community health workers in rural Malawi. Your implicit or explicit assumption may be that these health workers have a (recent-model) smartphone. Do they? Maybe not. If not, would that have a big impact? Yes, your app would be useless.

That brings us to step four: learn! With a list of the assumptions, put the riskiest at the top. Now design ‘experiments’ to as quickly and cheaply as possible figure out if your assumption was correct (“validated”) or incorrect (“invalidated”). Keep in mind that you do not need to spend 100% of the time to be 100% sure: this is not academic research for a peer-reviewed article in the Lancet! We only want to learn enough to get the risk to an acceptable level. And think of experiments in a broad sense: sometimes we can learn a lot by reading about the work that others already did (like indeed that scientific article) or talking to someone who already has the experience. But sometimes we do need to get “out of the building, into the field” to learn what is actually going on. And we need to do that in such a way that we get reliable and valid results. Doing this wrong is also a pitfall, but that is something for another post.

Then we go to step five. We document and share (=talk about) what we learned, process that into our explicit working theory, update the assumptions and risks.

And finally? We do it all over again! We iterate, well, from step two. The faster and cheaper we can do this, the better we are at innovation. This is what is called the ‘validated learning loop’, or the ’empirical approach’. I like to think of it as a ‘risk management’ approach. As innovation is so risky, it is our job to ‘de-risk’ it as quickly as possible.

Some ‘young’ (inexperienced) founders then tell me: “But being an entrepreneur is all about taking risk. I want to take risk!” Yes, you absolutely do. And you are courageous for that. But why take unnecessary risks? That is called: being reckless!

Back to reality

Of course reality is more ‘muddy’ than the simple theory put here. The working theory is never discussed in full, and not with the entire team. Visuals are incomplete and are rarely updated. Assumptions are defined on various level of abstraction and detail, overlap and contain other assumptions. Designing good experiments is complex, has many pitfalls and is more a creative art than a scientific process. And finally, articulating learnings from experiment is difficult and takes a lot of time.

Still, innovation means getting better at this process. Making a more conscious choice following this process will get you to success. It will make you ‘consciously competent’ at innovation. In the end, we will come to ask you to tell us your success story!

– Diderik